Sem 02 | Settlement Studies

Mirya, Ratnagiri, Maharashtra

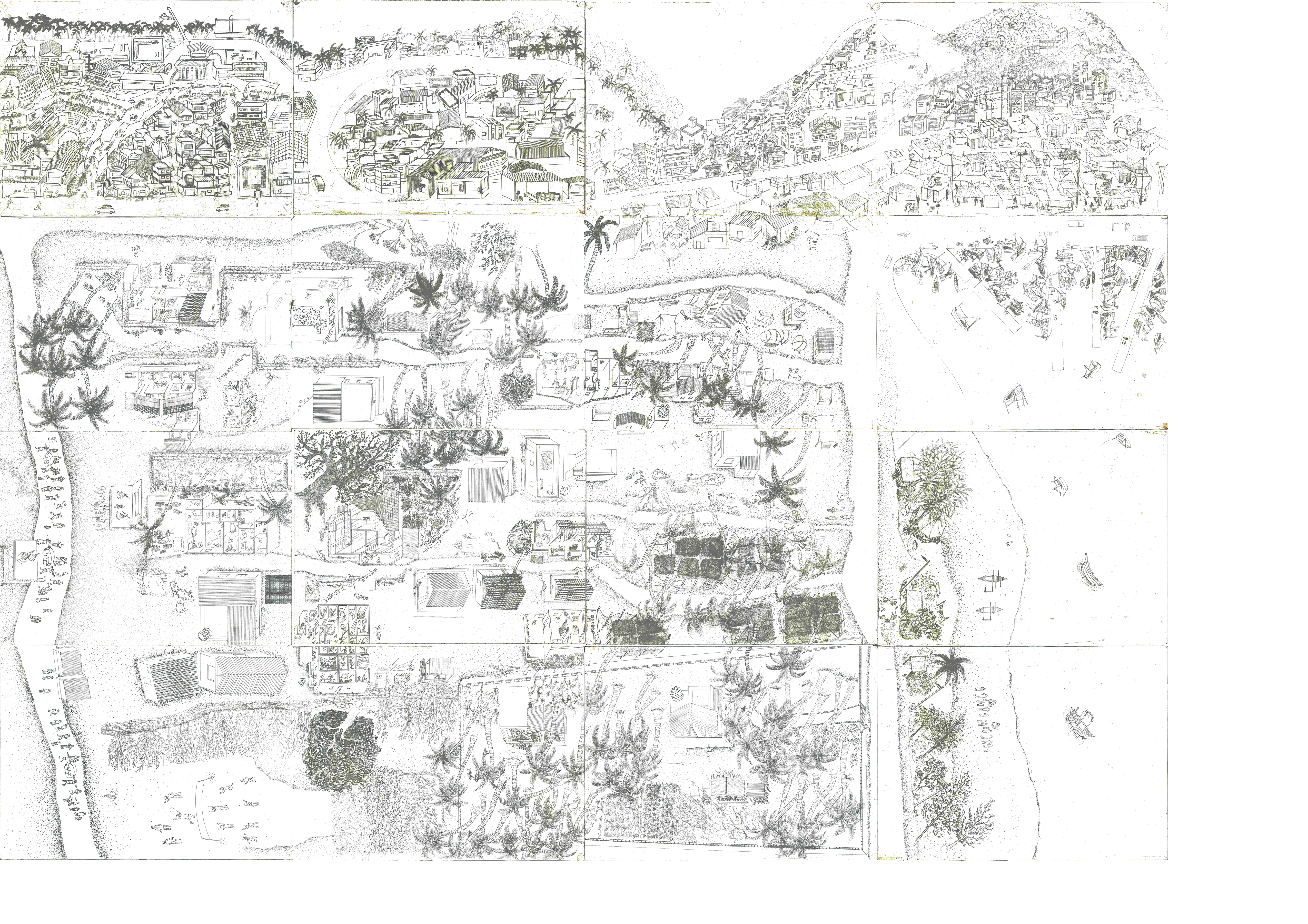

Apurva Talpade

Some summary notes accumulated from various conversations and discussions amongst students and teachers on site at Mirya, Ratnagiri

Mirya is a village caught between its enduring history as a settlement subsiding on the basis of a primary economy of fishing and its new role as an ancillary outpost of the city of Ratnagiri, serving its transforming economic needs.

This proto-urban / early urban stage of urbanisation is what we see. Where the idea of the “native” and largely of community are still felt keenly (seen in some continuing practices of built form, cultural objects, and construction details). However, a spatial transformation is seen as well, in the emergence of specific living rooms / bedrooms / dining rooms within the space of the house, in the transforming nature of the material of the house itself, in the spaces outside (erstwhile so central to everyday practices) getting neglected, in the accumulation of garbage in _____ , etc.

What are the changes that the economy is producing in built form?

The notions of permanence, privacy and property are consolidating, rendered visible in the appearance of boundary walls in the village.

The porous house, where life was lived continually between the outside and inside, where the commons played an important role in the fostering of social ties between neighbours, is now changing into a more bounded entity, leading to a solidification of the formerly nebulous notion of a family as well.

The introduction of newer construction materials are attached to new, urban images of the house - one with cement plastered walls, flat roofs, and a clearer segregation of internal functions.

In everyday life, bathrooms are entering the main complex of the house. Water is piped straight to the homes and so wells are left unused. A certain kind of encounter becomes limited - a diminishing sociality brought about by the development of infrastructure.

The notion of security is no longer in community but in savings and assets. However, the logic of a pastoral god continues, rituals and customs are still important in making visible established hierarchies, and older buildings housing older families continue to be politically relevant, all the while new conflicts arise between new groups and old groups that seek dominance in the evolving economic modes. This somewhat muddles the idea of Mirya being either entirely pastoral or actively urbanising.

We come to describe it as an “urbanising flux”. Mirya is in precisely this flux, its environment, pactices, and workforms all rapidly evolving. What is the architecture of this flux? The task of the settlement studies module is to identify that shift, find its evidence, and to draw it, and in drawing it hold not just a survey of its building practices and houseforms, but also its everyday, its routines and customs, and the relationships between builtform and social form.