SEA Conversations | Monsoon 2023-24

Drawing Worlds

Apurva Talpade

The concern for this series of SEA Conversations titled Drawing Worlds was with the question of drawing. It is one that the college holds very important, the pedagogy of the school is constantly trying to wrest new meanings, new forms, new ways for all of us, students, teachers, practitioners at all stages to consider the act as well as the object of drawing - specifically because it seems to be so limited when it comes to the discipline of architecture. These limitations in the consideration of drawing often establish themselves as constraints in spatial imagination itself and this series hoped to open up, by looking at drawing practices closely, how various ways of seeing engender new forms of imagination that reorient you and open possibilities to consider our world (and our spaces) anew.

Certain questions brought up in this series perhaps chart the ground that the conversations were able to cover. I deliberately leave you with the questions as an invitation to look closely at the practices of these artists in the videos linked here.

For Rohini Devasher, who is an artist and amateur astronomer.

Q: “The question of watching the watchers since the work is directed towards things that see - the camera is turned on itself, questions are asked of the astronomers, there are photographs of the observatories from a distance, the act of looking itself is brought into question, there is a close scrutiny of that essential act by looking at practices and devices and instruments that mediate looking or embody that. What new knowledge about looking, and how we see does that bring up in your work?”

For Afrah Shafiq who spoke of how tracing patterns in existing material and the study of lines, grids, motifs and repetition can lead to newer and endlessly emergent ways of meaning making.

Q: “What the work in the game world provides, and what the practice has also tried to engage is the question of uncertainty. When one is considering all the histories and following those trajectories, it becomes a powerful means of making a work interactive, which so much of it is. There are alternatives possible and everything happens in this fictive realm, but coming from questions and concerns that are historical -

And it sets up a curiosity that becomes an invitation that is present in the drawing itself. Could you speak a little about how that what if question emerges, how do you make that a way of seeing and also a way of drawing?”

Q: “The question of watching the watchers since the work is directed towards things that see - the camera is turned on itself, questions are asked of the astronomers, there are photographs of the observatories from a distance, the act of looking itself is brought into question, there is a close scrutiny of that essential act by looking at practices and devices and instruments that mediate looking or embody that. What new knowledge about looking, and how we see does that bring up in your work?”

For Afrah Shafiq who spoke of how tracing patterns in existing material and the study of lines, grids, motifs and repetition can lead to newer and endlessly emergent ways of meaning making.

Q: “What the work in the game world provides, and what the practice has also tried to engage is the question of uncertainty. When one is considering all the histories and following those trajectories, it becomes a powerful means of making a work interactive, which so much of it is. There are alternatives possible and everything happens in this fictive realm, but coming from questions and concerns that are historical -

And it sets up a curiosity that becomes an invitation that is present in the drawing itself. Could you speak a little about how that what if question emerges, how do you make that a way of seeing and also a way of drawing?”

For Nora Wuttke, social anthropologist and architectural designer, using her art practice as a mode of enquiry in her academic research.

Q: “Drawing as, the “as” being an important coordinate to open up to discuss where in this work it seems that one could see the drawing as a dialogue with the surroundings. Now that dialogue, because it is the field and the field is an unwieldy thing is not always the most settled and peaceful thing. The dialogue is an argument and the dialogue is a dispute. Then, how is the drawing affected by this shifting nature of the kinds of presences that the field is bringing out? Since in this kind of work, one is getting to know your surroundings in this strange way and, even stranger, the surroundings are getting to know you.”

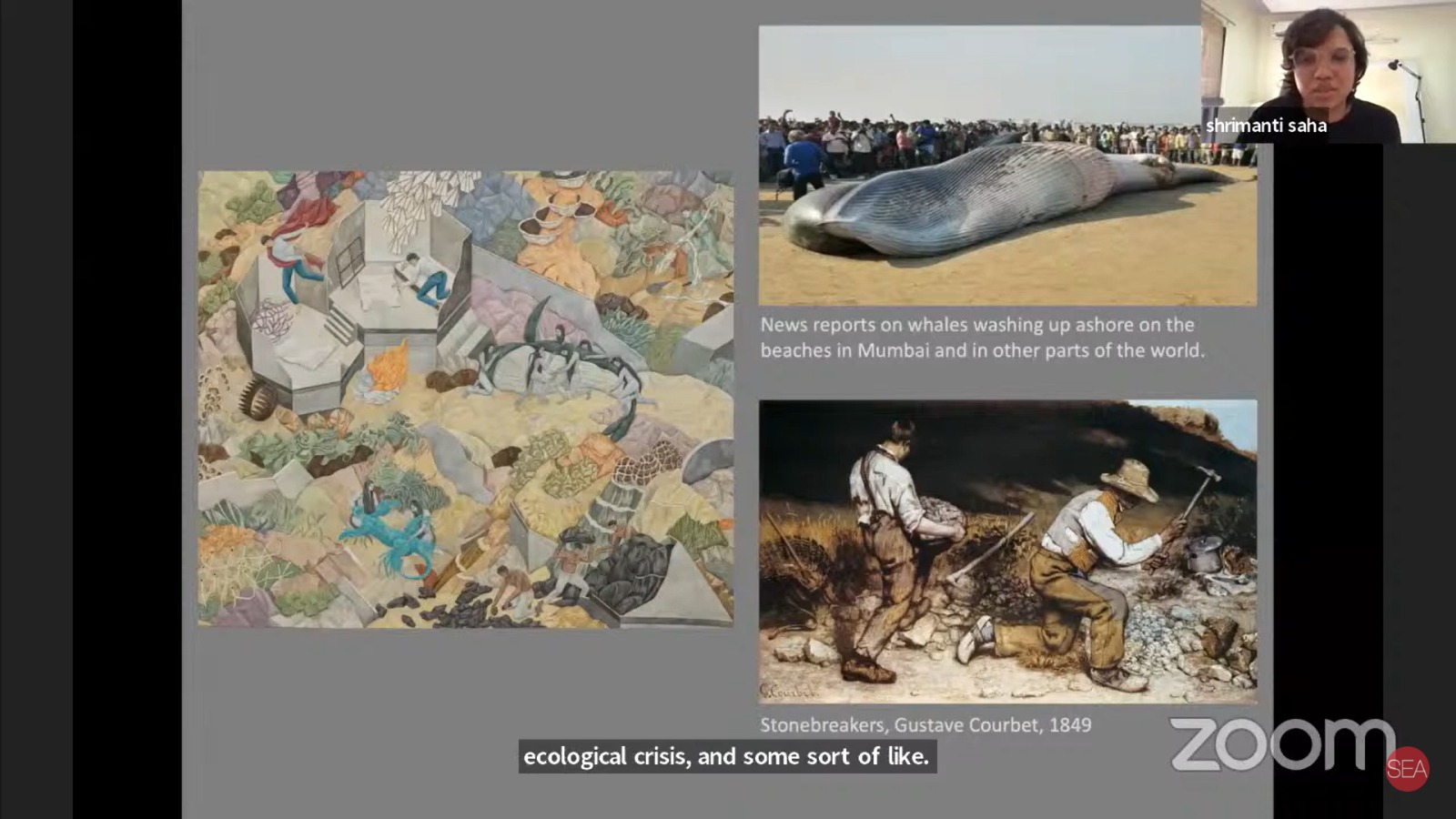

For Shrimanti Saha, who is an artist working in the medium of drawing, painting and animation

Q: “The works are beautiful and cartographic - they’re inevitably landscapes with the impulse of the map coded within it. What is the measure of the map, or the values of the map through which the cartography gets made here? Since the map is a metaphor for the territory and represents the culture that created it, in a lot of ways the work behaves as a map.”

(This question is in reference to ways in which many older communities make maps - where the knowledge interest is not in measurements but in more “abstract” or “moral” concepts like “secrets”, “sins”, “obligation”, “order”, etc.)

For Sayan Skandarajah, whose talk engages with the role of architectural representation in seventeenth-century screen paintings of Kyoto, Japan, aiming to test and examine the implied spaces of the city that were defined by the original artists.

Q: “Narrative traditions in drawing also hold forms that the Indian subcontinent has seen - where for example we have an indigenous drawing practice like Warli painting, or miniature drawings that have multiple perspectives of showing space that use a logic which is not the geometrical logic of the perspective, but seems to say that there are no fixed points in space, or the fact that they are built as this composite of layers, where you have an overlapping of people and objects and settings to produce the space of the image as one of the complex which is also how actual space gets put together - there are a related group of buildings and the relationships between them may be entangled in how you navigate them…

What are the ways in which your drawing - which is setting out to complicate and inhabit the nature of the city that the screens set up - one which perhaps is about a hierarchy of space and habitation, what is the nature of space that it is arguing for - what is the spatial proposition that gets made about what makes the built environment come together?”

Q: “Drawing as, the “as” being an important coordinate to open up to discuss where in this work it seems that one could see the drawing as a dialogue with the surroundings. Now that dialogue, because it is the field and the field is an unwieldy thing is not always the most settled and peaceful thing. The dialogue is an argument and the dialogue is a dispute. Then, how is the drawing affected by this shifting nature of the kinds of presences that the field is bringing out? Since in this kind of work, one is getting to know your surroundings in this strange way and, even stranger, the surroundings are getting to know you.”

For Shrimanti Saha, who is an artist working in the medium of drawing, painting and animation

Q: “The works are beautiful and cartographic - they’re inevitably landscapes with the impulse of the map coded within it. What is the measure of the map, or the values of the map through which the cartography gets made here? Since the map is a metaphor for the territory and represents the culture that created it, in a lot of ways the work behaves as a map.”

(This question is in reference to ways in which many older communities make maps - where the knowledge interest is not in measurements but in more “abstract” or “moral” concepts like “secrets”, “sins”, “obligation”, “order”, etc.)

For Sayan Skandarajah, whose talk engages with the role of architectural representation in seventeenth-century screen paintings of Kyoto, Japan, aiming to test and examine the implied spaces of the city that were defined by the original artists.

Q: “Narrative traditions in drawing also hold forms that the Indian subcontinent has seen - where for example we have an indigenous drawing practice like Warli painting, or miniature drawings that have multiple perspectives of showing space that use a logic which is not the geometrical logic of the perspective, but seems to say that there are no fixed points in space, or the fact that they are built as this composite of layers, where you have an overlapping of people and objects and settings to produce the space of the image as one of the complex which is also how actual space gets put together - there are a related group of buildings and the relationships between them may be entangled in how you navigate them…

What are the ways in which your drawing - which is setting out to complicate and inhabit the nature of the city that the screens set up - one which perhaps is about a hierarchy of space and habitation, what is the nature of space that it is arguing for - what is the spatial proposition that gets made about what makes the built environment come together?”

For Parismita Singh, whose talk looked at drawing as a practice shaped by political exigencies and history, and reflected on the ethical and aesthetic negotiations that are a part of it.

Q: “An excerpt from an interview by Donna Haraway goes: ‘I love words that just won’t sit still, and once you think you’ve defined them it turns out they are like ship hulls full of barnacles. You scrape them off, but the larvae re-settle and spring up again. Figuring is a way of thinking or cogitating or meditating or hanging out with ideas. I’m interested in how figures help us avoid the deadly fantasy of the literal. Of course, the literal is another trope, but we’re going to hold the literal still for a minute, as the trope of no trope. Figures help us avoid the fantasy of ‘the one true meaning’. They are simultaneously visual and narrative as well as mathematical. They are very sensual.’

It seems as if the excerpt is constantly throwing up these metaphors of how stories settle and shift, and also blurring the distinction between writing and drawing by using this happy, chance word, “figuring” that conjures up both ideas of wrestling with ideas, words, and invoking the suggestions of the drawn. And mostly because she uses the phrase “deadly fantasy of the literal”, which is a task that drawing takes on very successfully…

How do you make for yourself the “Thinking-writing-drawing as a kind of sympoiesis” that is more interested in world making than the “literal”? How do you decide where to rely on what? What distinctions do you make between forms?”

Q: “An excerpt from an interview by Donna Haraway goes: ‘I love words that just won’t sit still, and once you think you’ve defined them it turns out they are like ship hulls full of barnacles. You scrape them off, but the larvae re-settle and spring up again. Figuring is a way of thinking or cogitating or meditating or hanging out with ideas. I’m interested in how figures help us avoid the deadly fantasy of the literal. Of course, the literal is another trope, but we’re going to hold the literal still for a minute, as the trope of no trope. Figures help us avoid the fantasy of ‘the one true meaning’. They are simultaneously visual and narrative as well as mathematical. They are very sensual.’

It seems as if the excerpt is constantly throwing up these metaphors of how stories settle and shift, and also blurring the distinction between writing and drawing by using this happy, chance word, “figuring” that conjures up both ideas of wrestling with ideas, words, and invoking the suggestions of the drawn. And mostly because she uses the phrase “deadly fantasy of the literal”, which is a task that drawing takes on very successfully…

How do you make for yourself the “Thinking-writing-drawing as a kind of sympoiesis” that is more interested in world making than the “literal”? How do you decide where to rely on what? What distinctions do you make between forms?”

For Jasmine Nilani Joseph, who speaks of the impact that Sri Lanka’s political history has had on the space of her village Jaffna through her drawings.

Q: “The questions in the practice are specific and lucid and intimately tied to the questions of space. Of what sites and buildings and terrains provide us with in terms of belonging, and what that loss can give you in terms of a method of seeing. The work has always been spoken about as addressing the feelings of loss and displacement - these losses of the space of the home and the neighbourhood. The ways of seeing that get set up in the drawing however, have built in them this register of distance. Historically, the orthographic drawing systems, the plans and elevations, suggest this sense of being at a common continuous distance from the thing being mapped at all times. Which again, when one speaks of visiting something that is familiar, but from behind the fences, it does necessitate this kind of detachment perhaps? Or maybe the elevations also speak of mapping methods used by institutions - surveys, and land use maps and so on… How does this way of seeing allow you to determine for yourself the ways in which you can bring an intimacy into the work? How do you resolve both, the highly personal nature of what is being drawn, to the measured mapping method of drawing in orthographic projections?”

Q: “The questions in the practice are specific and lucid and intimately tied to the questions of space. Of what sites and buildings and terrains provide us with in terms of belonging, and what that loss can give you in terms of a method of seeing. The work has always been spoken about as addressing the feelings of loss and displacement - these losses of the space of the home and the neighbourhood. The ways of seeing that get set up in the drawing however, have built in them this register of distance. Historically, the orthographic drawing systems, the plans and elevations, suggest this sense of being at a common continuous distance from the thing being mapped at all times. Which again, when one speaks of visiting something that is familiar, but from behind the fences, it does necessitate this kind of detachment perhaps? Or maybe the elevations also speak of mapping methods used by institutions - surveys, and land use maps and so on… How does this way of seeing allow you to determine for yourself the ways in which you can bring an intimacy into the work? How do you resolve both, the highly personal nature of what is being drawn, to the measured mapping method of drawing in orthographic projections?”

The following talks were conducted in this series:

Talk 1/ Rohini Devasher - Fungi -> Firmament: Drawings from the Field

July 05, 2024.

Talk 2/ Afrah Shafiq - Literal and Metaphorical Patterns

July 19, 2024.

Talk 3/ Nora Wuttke - Drawing Relationships: Drawing as Research Method

August 02, 2024.

Talk 4/ Shrimanti Saha - Multifaceted Narratives

August 16, 2024.

Talk 5/ Sayan Skandarajah - Drawings as Sites, Sites as Drawings

August 30, 2024.

Talk 6/ Parismita Singh - The Wayward Line and Other Adventures in Image Making

September 27, 2024.

Talk 7/ Jasmine Nilani Joseph - Drawing: A Tool for Investigating Barriers and Shelters

October 04, 2024.

Talk 1/ Rohini Devasher - Fungi -> Firmament: Drawings from the Field

July 05, 2024.

Talk 2/ Afrah Shafiq - Literal and Metaphorical Patterns

July 19, 2024.

Talk 3/ Nora Wuttke - Drawing Relationships: Drawing as Research Method

August 02, 2024.

Talk 4/ Shrimanti Saha - Multifaceted Narratives

August 16, 2024.

Talk 5/ Sayan Skandarajah - Drawings as Sites, Sites as Drawings

August 30, 2024.

Talk 6/ Parismita Singh - The Wayward Line and Other Adventures in Image Making

September 27, 2024.

Talk 7/ Jasmine Nilani Joseph - Drawing: A Tool for Investigating Barriers and Shelters

October 04, 2024.