Allied Studies / Rohit Mujumdar

Bodies, Cities, Ecologies

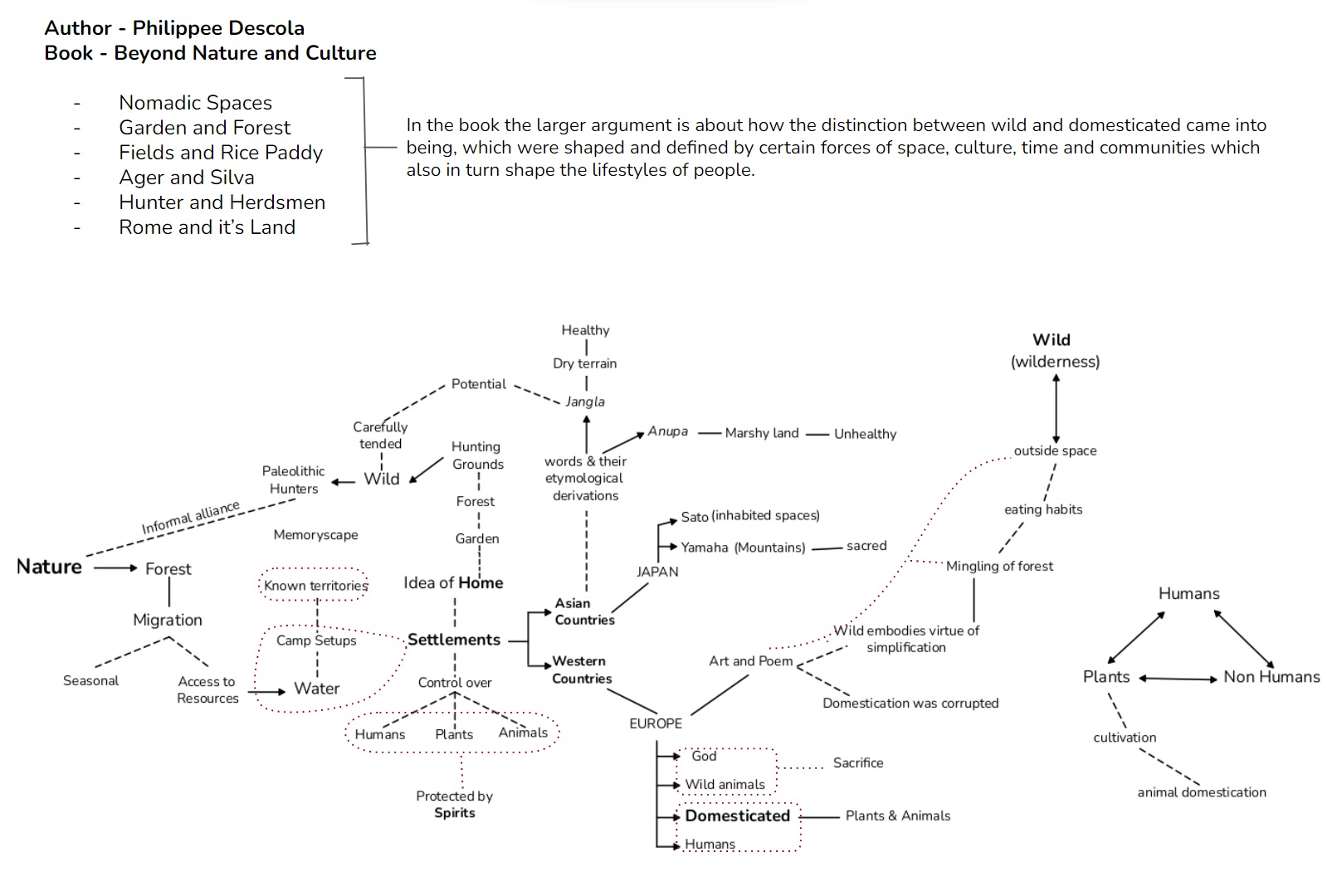

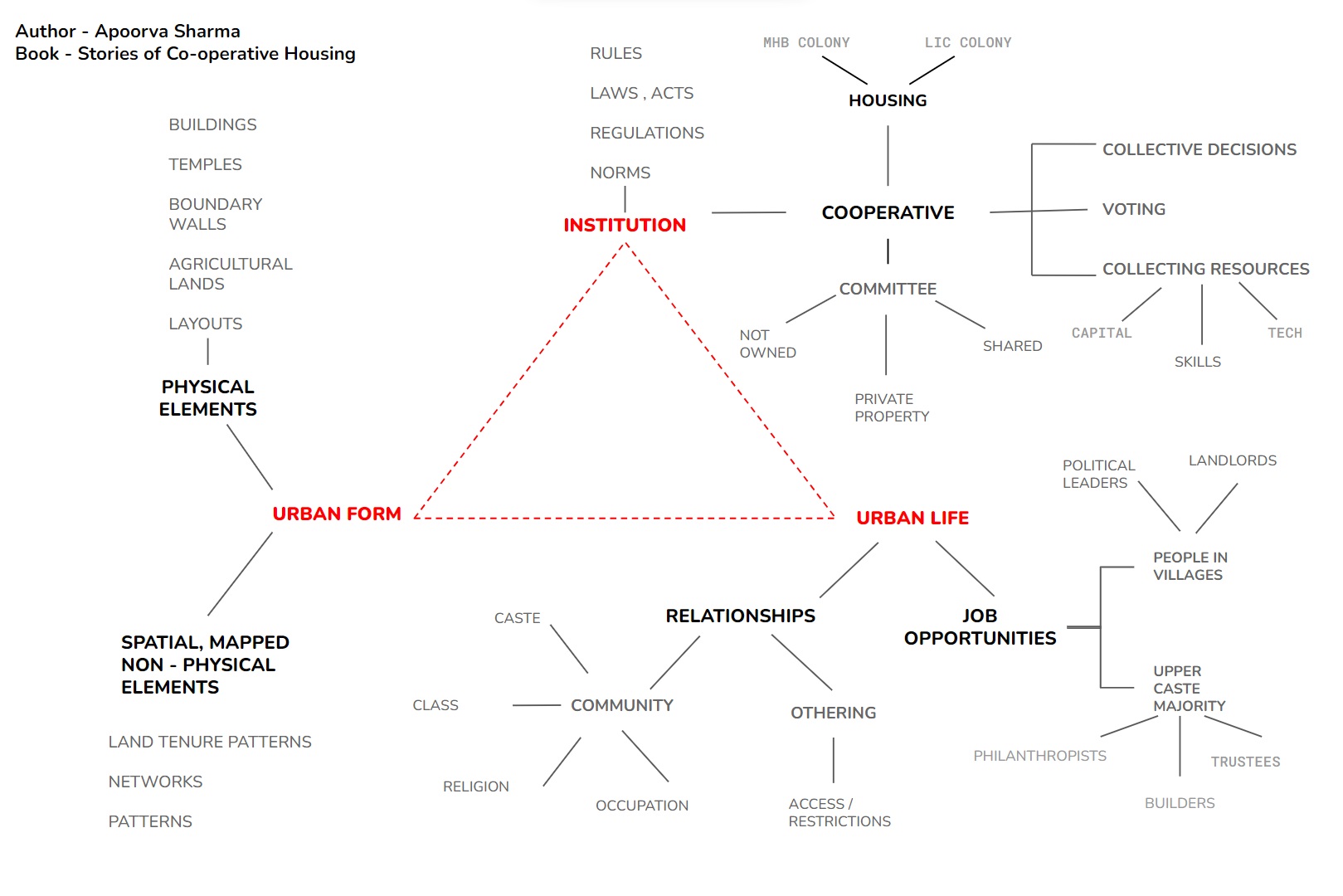

Postcards from Mumbai and NairobiIn this three week long Bodies, Cities, Ecologies course, our goal explored the ways in which bodies marked by the differences of caste, religion and gender, and the spaces of city neighbourhoods and their ecologies shaped one another. We approached our goal by setting week-long teaching and learning objectives to achieve the overall course goal. In the first week, we read four texts to situate ourselves in questions of difference, space and ecology. In reading this scholarship, students shared notes to produce a short response paper. In their response, students articulated the questions that emerged for them through the reading of scholarship.

Student questions culled from readings

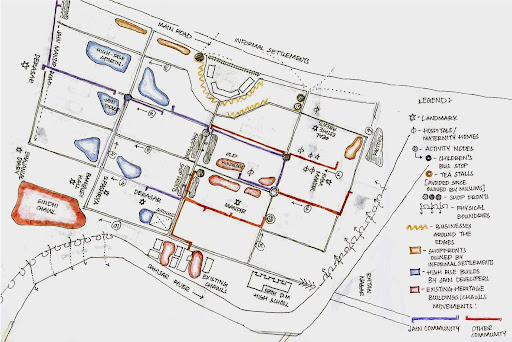

We used the evenings to walk three neighbourhoods along Dahisar river where we would explore our course goal through a field-based inquiry. During the second week, students conducted fieldwork in two of these neighbourhoods— a vasti along a mangrove edge and a privately plotted town planning scheme besides the river—based on the questions they articulated through the reading of scholarship, on the one hand, and through the field-based engagement, on the other hand. The objective of conducting this fieldwork was to draw out stories through short vignettes of 250 words accompanied by a photograph or drawing. During the third week, students compiled these narratives in the form of picture postcards, which could be read together to engage in a conversation about socionatures.

Four kinds of stories emerged from the vasti:

queer practices of faith and spirituality;

queer practices of faith and spirituality;

“Unka gussa bohot khatarnak hai.!”

“Unka gussa bohot khatarnak hai.!” “Jab bhi Aai khelne aati thi na woh mujhe sab batata tha, ki aage kya hone wala hai.”

“Jab bhi Aai khelne aati thi na woh mujhe sab batata tha, ki aage kya hone wala hai.”

complexities of tenure, surveillance and security

Gully number one to four falls under the SRA scheme. As one goes from the main road towards the mangroves, more corners and small pockets are created. The families living in this area have both the man and woman working in hospitality and services in the neighbouring locality. They have electric and water supply in all the houses.

As the settlement grew and formed quieter pockets, crime and abuse also began to fester in these spaces which led to the rent of the gully being lowered as rumors began to float amongst the residents about the conditions of the gully changing at night. A majority of cameras were installed by ‘the owner’ to cease the rumours that were spreading and to balance the rent.

As the settlement grew and formed quieter pockets, crime and abuse also began to fester in these spaces which led to the rent of the gully being lowered as rumors began to float amongst the residents about the conditions of the gully changing at night. A majority of cameras were installed by ‘the owner’ to cease the rumours that were spreading and to balance the rent.

gendered practices to share resources;

Water is a valuable resource in the settlement as piped municipal water supply is limited to an hour each day. Around five to six households depend on a solitary tap for their daily water requirements.

Women from the households adjacent to the baoli actively choose to grow plants and trees around it.

While men contractors construct houses and baolis from stone, cement and asbestos sheets, women design, cultivate and tend to the landscape of the narrow lanes around baolis with plants and trees.

and, even about practices to soften and make a harsh landscape hospitable to everyday life.

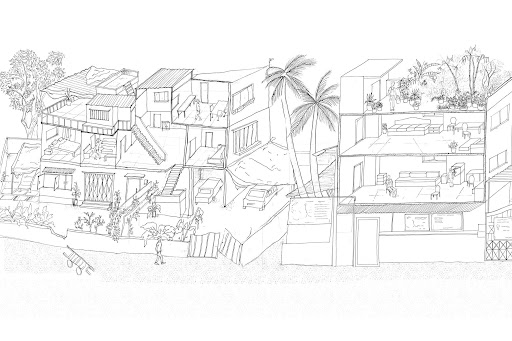

In a settlement where space is already scarce, various methodologies of claiming space begin to form. One such instance occurs at the far end of gully no.14, where a resident has extended his house to form a garden. He has claimed the land in front of his house by landfilling the creek and building a garden. Various such interventions have emerged that not only soften the harsh conditions that exists within the settlement but also allow the residents to claim their space.

The privately plotted town planning scheme unraveled four kinds of stories about the intersections of religiosity and everyday life of apartments:

stories of notional boundaries and amenities shaped by practices of religiosity;

stories of notional boundaries and amenities shaped by practices of religiosity;

The blunt contrast of newly built modern housing apartments with amenities that entice one to utilize the most of it and the old mellow bungalows and 2 stories building with their intimate spaces that appeal to socialization and play has created invisible boundaries between communities and people , where the mental map of the neighborhood explains how their extent of routine is held back to specific areas.

the transformation of the apartment type due the practices of religiosity and the spatial affordances it offers;

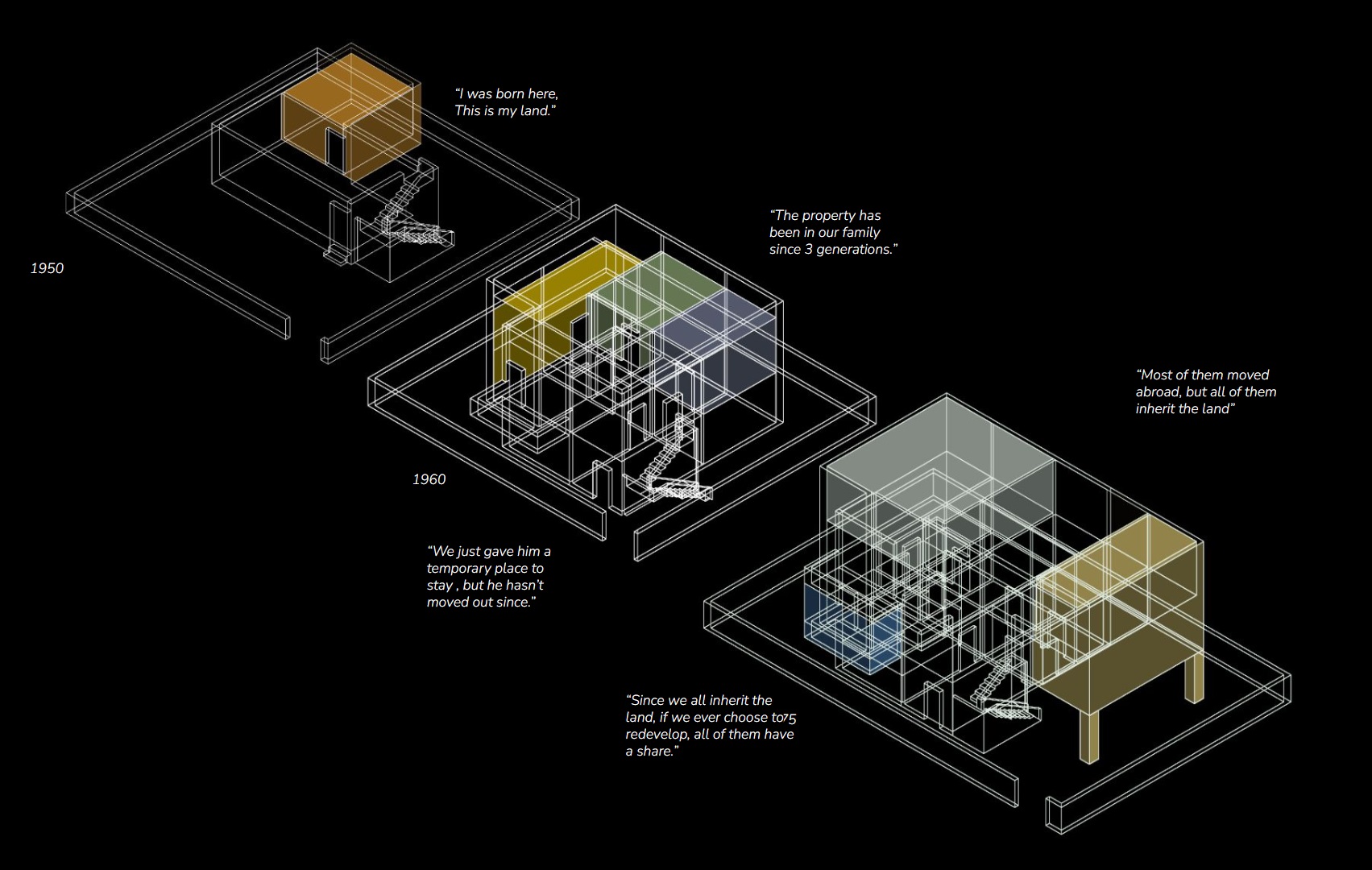

and, the complexities of stakes involved in the transformation of the former bungalow type into apartments;

" We are one big family, not 17 families ", says Edmund while walking us through his 60 year old bunglow, located on road no.5 in Daulat Nagar. Edmund Sunil Lazez, born in 1960, is a dedicated employee of Bombay Diocesan Trust Association.

“The land has been in our family for 3 generations,” Edmund explains. “The land was purchased by my grandfather from Seth daulatram , grandfather was a Dean in Gujarat during British raj. He moved here to Bombay with his 5 sons and two daughters, in the search of a good education”. The initial bungalow which was built in the 1960s was only ground floor , later as the family grew they added more floors. His grandfather added an extension to the original building for his aunt, Later in the late 70s. While Edmund is an only child , he has 5 cousins. “Since we all inherit the land , if we ever choose to redevelop the land , all of them have a share”.

“The land has been in our family for 3 generations,” Edmund explains. “The land was purchased by my grandfather from Seth daulatram , grandfather was a Dean in Gujarat during British raj. He moved here to Bombay with his 5 sons and two daughters, in the search of a good education”. The initial bungalow which was built in the 1960s was only ground floor , later as the family grew they added more floors. His grandfather added an extension to the original building for his aunt, Later in the late 70s. While Edmund is an only child , he has 5 cousins. “Since we all inherit the land , if we ever choose to redevelop the land , all of them have a share”.

and, practices to soften a densifying and hard builtform due to practices of redevelopment.

The house which was initially a one floor terrace is now a three floor terrace since 2000. After these changes the ground was utilized for more commercial purposes , but Deepak ji was too attached to the garden just to leave it like that. So, he shifted the whole thing on his terrace .

The garden on Deepak ji's terrace is a collection of various plants which Deepak ji himself handpicked. From neem, to okra, to bamboo, they occupy the floor, the parapet, the walls, and also the chimney, almost blurring the builtform of the terrace.

The garden on Deepak ji's terrace is a collection of various plants which Deepak ji himself handpicked. From neem, to okra, to bamboo, they occupy the floor, the parapet, the walls, and also the chimney, almost blurring the builtform of the terrace.