Allied Studies, Apurva Talpade

The Scribe and The Labyrinth

or

Developing artistic documentary practices around the critical everyday

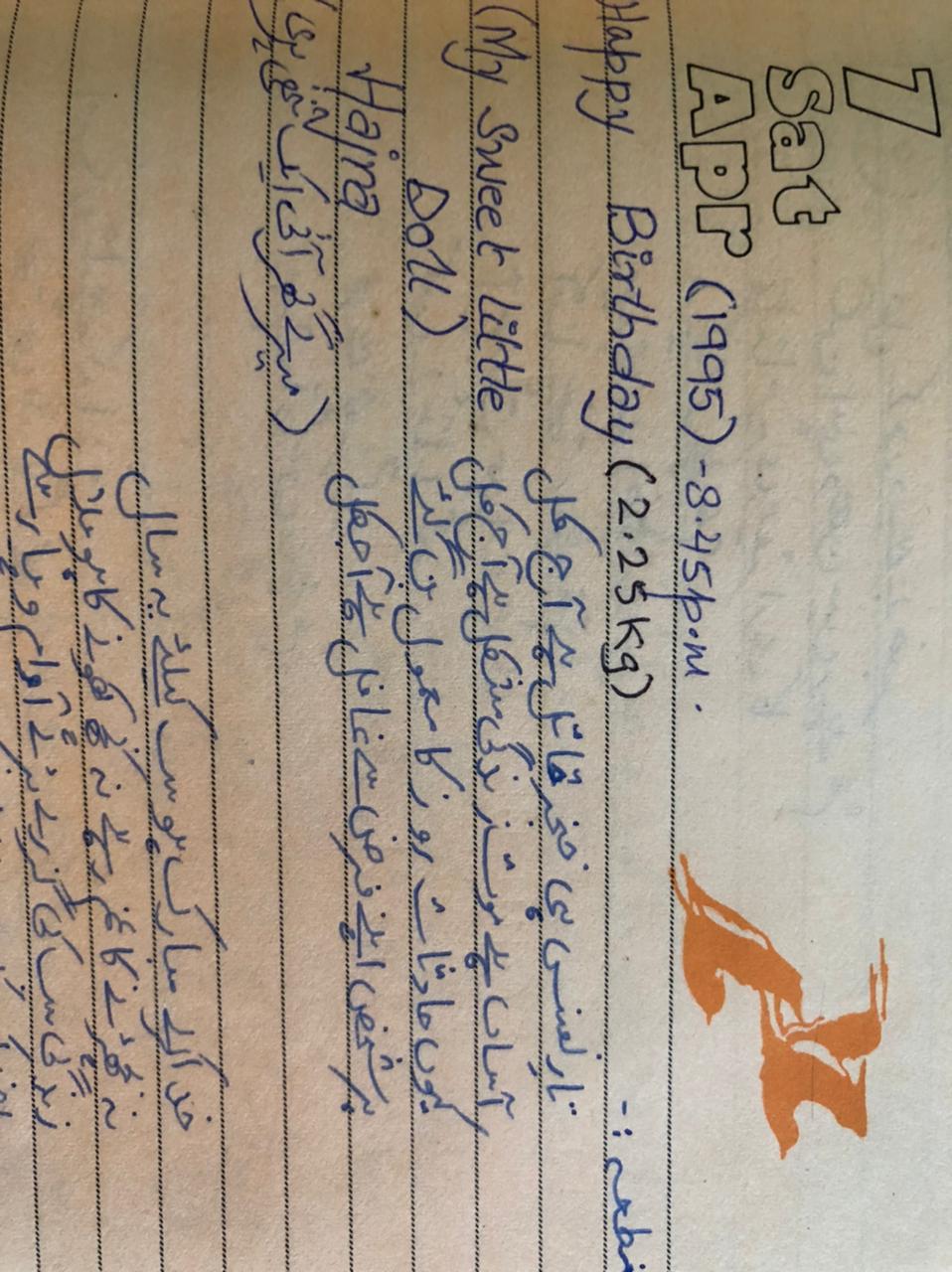

Maryam Sheikh

Your chosen practice is the interruption and extension of everyday conversations by the shayars. This is a continuation of the practice that your grandfather inculcated in you and you pay homage to it now by staging these conversations. The works describe a situation or an event in the everyday, hijacked by a poem or a couplet, that then takes you to another memory. The audios try to build a sense of this memory through slow, deliberate descriptions and you can feel the presence of your grandfather in corners of the memory. How will you construct this? The potential for the string of memories to grow is infinite. Some of them can have multiple memories, changing scenes like in a surreal play. The idea is that this practice allows you to reflect on the ways in which your grandfather makes his presence felt, while allowing the conversations to become an archive of the opportunities in everyday conversations to make poetry relevant.

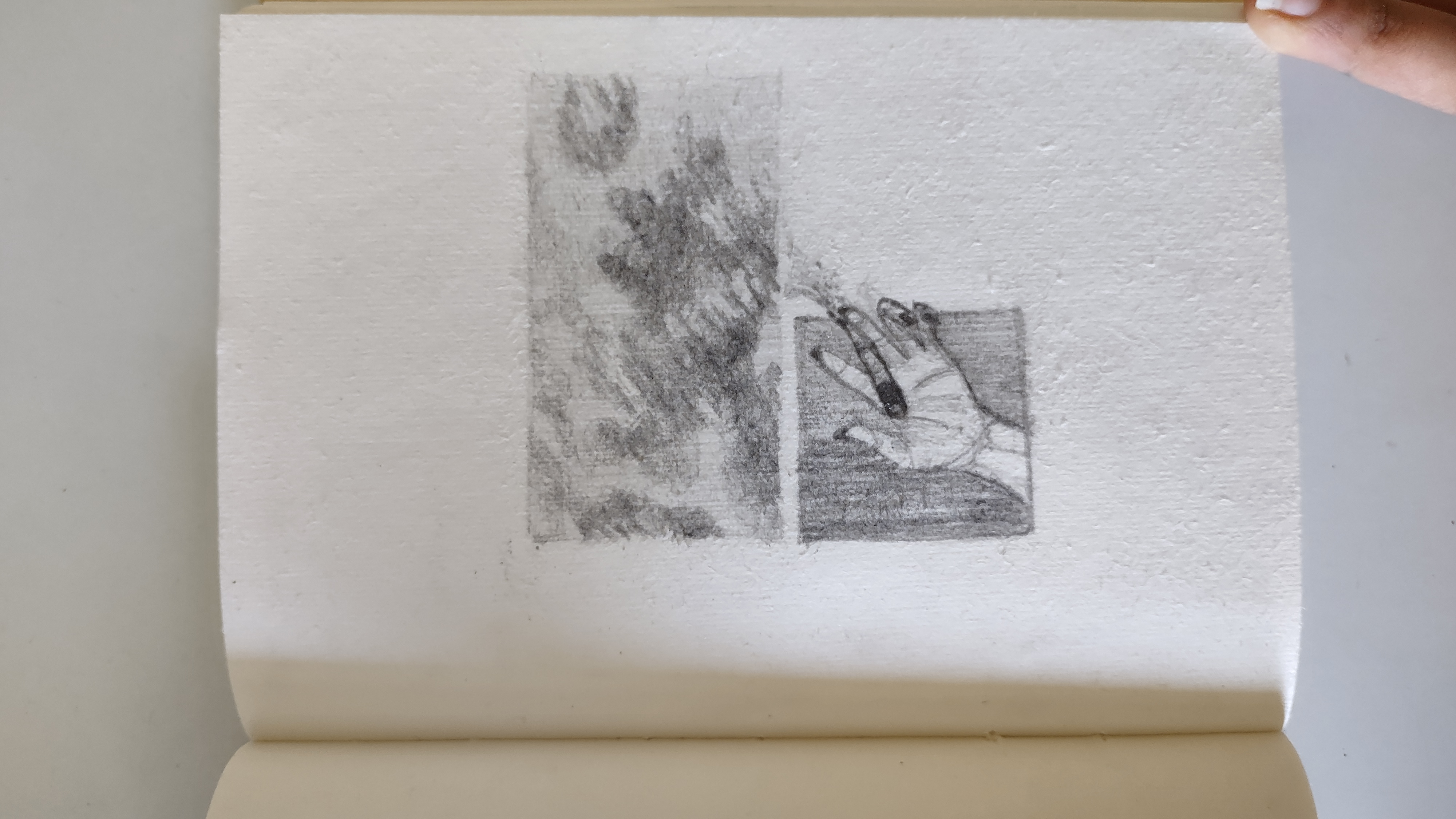

Shriya Parab

You are expanding on an already existing drawing practice. The forms that the drawings now take are those of these silent narratives that look closely at life around you. What emerges is the idea of the "non event" that is able to take on another dimension altogether, because of how you look at it. You see the everyday as constructed of several of these small events - the father pulling his son back home, a specific crow that visits the branch of the tree, a sign that talks of the changing of the season, you spilled half over the edge of your sofa, many many kinds. What happens with these books is that it lets you look at the everyday at a granular level, examine small practices, small resistances, small pleasures, and build a generous document of them.

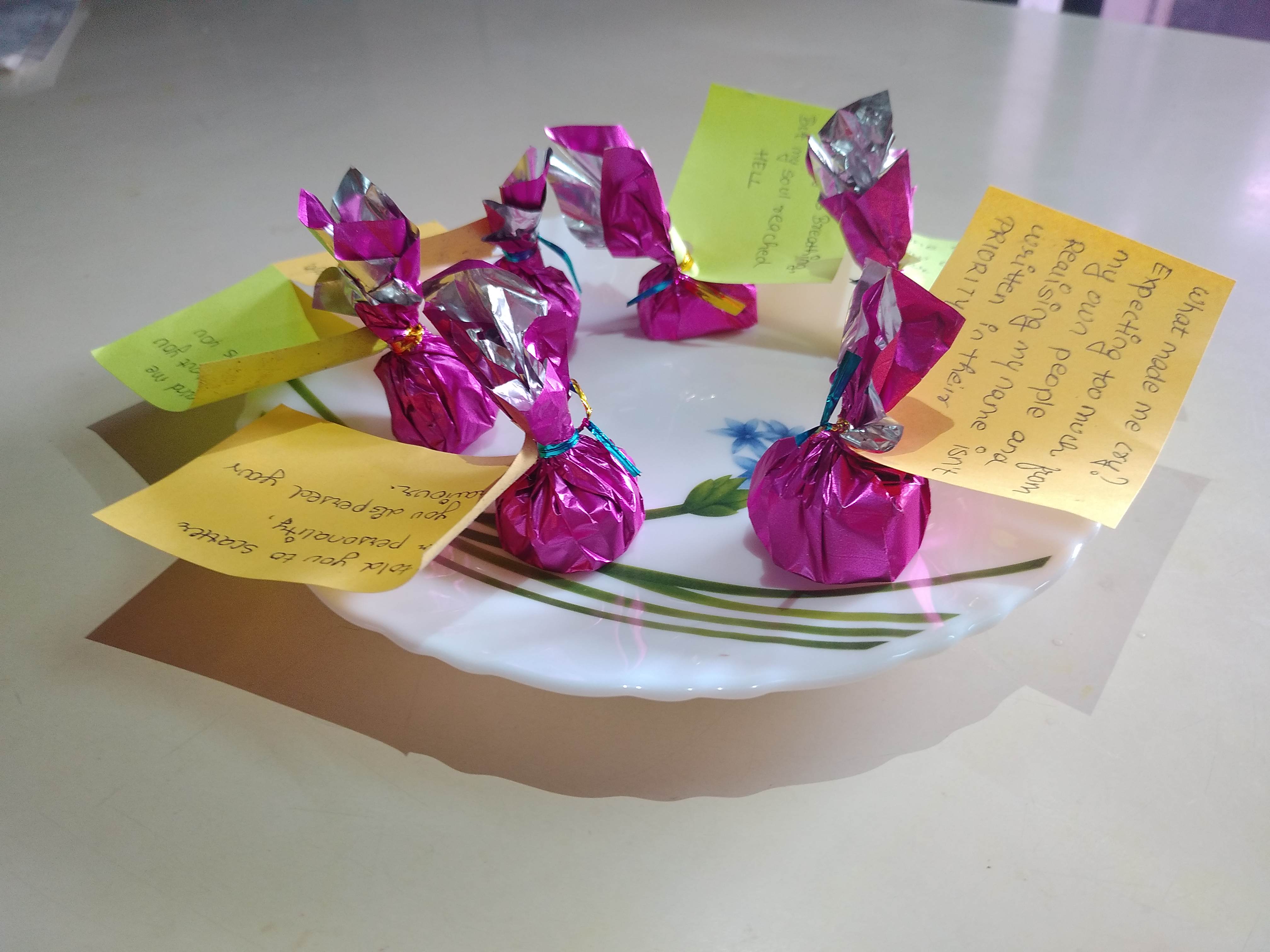

Sayali Zantye

There is a strong focus on the world of sentiment in your work. These are at the forefront of the explorations in your poetry as well, you use your feelings to describe what moves you, and how it moves you. This is done through the two-fold practice of drawing, as well as writing poetry. These work together in strange ways - the drawings are almost cartoon like images, always uniform, that offset the experiments in the writing. In order to stage the production, you think of these works as ubiquitous, appearing everywhere and unexpectedly in your routine. Therefore, you see them on the clothes-line, among the vegetables, on the backs of labels of jars in the kitchen. The sense here is that the feelings take over the routine, they take over the mundane, they wrap themselves around everything and muffle and soften the familiar shapes and forms all around you.

Anika Pugalia

The ukulele and your fondness for sound, especially song, is something that pervades all other practices, all other spaces, above all others. This is something that you carry out as an accompaniment to several aspects of your life - class, family gatherings, travel, etc etc. Since you are familiar with the idea of producing videos where you play the ukulele and sing, this becomes a new artistic direction for you. The filming of spaces is one that looks at small movements as those of comfort and familiarity - ways in which feet move under a table, positions that we take while watching TV, etc. Over all of these there is an environment that is created of sound which mixes domestic sounds, signs of everyday routine and ritual, with that of the ukulele playing (your own specific ritual). Filmed and put together, this becomes a work that explores and expands what could become the material for your own practice as a musician.

Neel Bothara

Since you have an existing, large photographic practice, what you attempt to do is build the archive. This is to look more closely at your own work - what are the patterns that emerge? What are your tendencies within photography? What are the subjects that most draw you? How do you practice a photography that looks at intimacy and space through the archive? How often do you seek escape? What are the kinds of photographs that correspond to the kinds of escapes? This is done through a careful cataloging of the photographs - you look at tags and cross referencing to look at the ways in which different combinations of "home", "neighbourhood", "July", "landscape" build a sense of life. This should ideally be accompanied by expanded notes on the same.

Netra Khodke

An archive of the sounds of the everyday, told through the experience of the sounds. All of these sounds are much more than dry labels - flush, tap, bell, curtains - but because your world is built through an attention to these sounds, your experience of the world is very reliant on sound, your sense of safety and being is built through how you perceive all of these. Therefore, the practice of observation or attentiveness to the details of all of these becomes central. You are able to thus construct poetic compositions through the arrangement of both words and sounds in the very mundane "playlist". This is a practice that can become collaborative. Another's poetry produces a completely different day for you, and also examines questions of the musical composition. What constitutes a "musical piece"? What is the experience of these new arrangements?

Avantika Padalkar

The sense here is that there is a potential for the surface of everyday life to simply crack and fall apart, revealing a world where superficial interactions give way to high intensities of crimes and passions. This is actually how crime works. The "criminal" is not someone who dresses in black, is a thug, swears at the world, is mean to animals, etc etc, but most often it is someone who lets slip the guard of social conduct that dictates how their violent urges and instincts are controlled. The surveillance footage allows for you to imagine these parallel lives. The goings and coming from the gate, the various windows that you film, all of them seem ordinary, but the energetic self in you is able to layer them with various stories, allowing for you to experience a more vivid form of life, where your interest in the paranormal / violent collapses onto the landscape of your immediate everyday.

Ruchita Sarvaiya

The attempt over the four weeks has been to try and find a form that uses, in different combinations, all the small practices that you hold dear - drawings and writings, notes that you write to yourself, images that connect you to events, images that spark long and detailed retellings of memories, among others. You've explored this in many ways as well. Through postcards that are built from material scraps and leftovers; through ways of drawing over images in order to see them as precious, bringing attention to specific aspects of the space / person; through writings overlaid on photographs; and, most recently, through the space of your room made into a year long, large scale advent calendar. Taking the form of paper cubby holes on your walls, this private postal system allows you to write to multiple selves in the future and past, revisit it as a living, material diary, gather ephemera beyond the paper scraps as remains of the day and have conversations that stretch through time via the calendar that houses all of these.

Smit Lakkad

The idea of living energetically has been relegated to the sidelines of your life - you make itineraries loosely connected to travel, but that actually seek a form of living that is about imagination and intensity. The practice for you is located in the idea that your neighbourhood, the spaces of your everyday are able to accommodate these grandiose ideas of life as well. Therefore, it becomes about an act of staging these fictional forms of life - that of an absurd, nostalgic idea of crime - and to allow the staging to blur the line between everyday life and the fiction, such that you end up living the fiction itself. The possibilities are endless - you are able to inhabit the "spy", the "gangster", the "lover", the "mystic", all of these roles, and produce a life that is an overlap between the fictional and the prosaic.

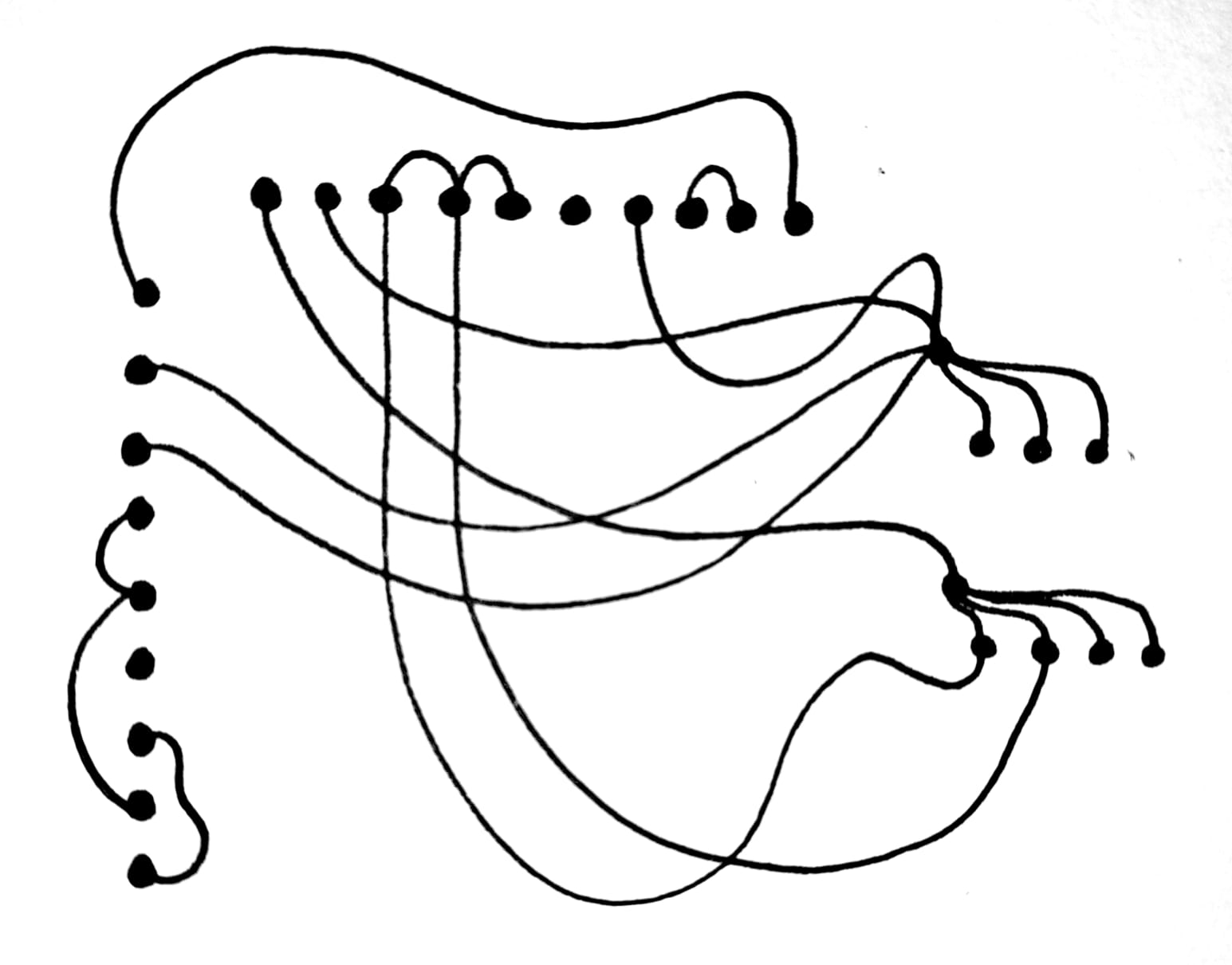

Riya Israni

The practice has taken you across a field of experiments with the material. These experiments have gone forward in ways that are unseen, often unpredictable and it is a constant give and take between intervening consciously and letting the direction of weaving take its own form. What this results in is a work that is sculptural, tracing landscapes, that doesn't lend itself to ideas of usefulness, rather its value is in simply being. The experiments have the potential of expanding in multiple directions, including various kinds of materials, the weave itself is able to give form and create structure and story through varying combinations. The artistic possibility lies in that yield and pull between conscious and subconscious forces working through the various weaves.

Grishma Mehta

Producing the walk as an aesthetic experience comes from you observing the walk as something you partake in everyday - not zealously or as a strict ritual, but as a gentle, everyday pleasure. In observing the walk carefully, what emerges are various kinds of accounts - notes on the textures of the pavement, stories around buildings that have longer histories than the slightly more uniform, redeveloped ones, multiple stories of small encounters between all kinds of urban life - human, animal, cars encountering pavements, trees encountering windows, etc. All this contributes to a new way of drawing, located across Situationist mapping, collating anecdotes, and experiences in a phenomenological drawing.

Jugal Kamalia

Using everyday objects and details in spaces as an anchor, your practice looks at drawing them as a system of contours in order to see them as landscapes. Sometimes, the landscape remains as a method to reconstruct the object, but there is the possibility for the subconscious to take over in the act of drawing, allowing the lines of the object to dissolve and for another landscape to emerge. This landscape can be read from its contours and valleys and other "land" forms but what is held onto is that the space of the drawing is a meditative space, and that this meditation is often trance-like, allowing you to bring forth all the wanderings of the subconscious self. The practice wants to explore what these landscapes look like.

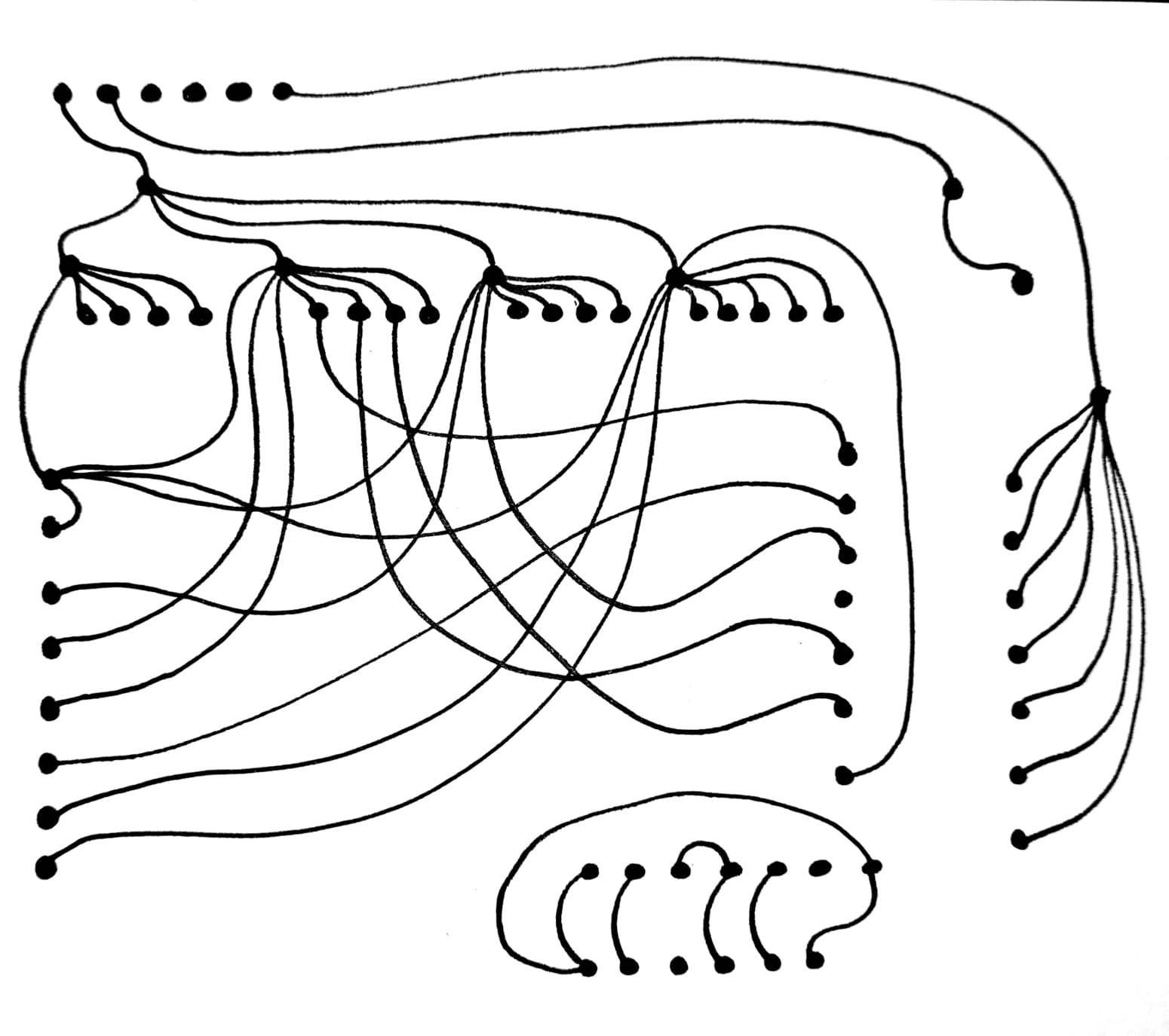

Tanushree Bhagwat

All the multiple ways in which you try and make sense of your life are present in your journals. These are all firmly entrenched in the logic of systems and measures that calculate and compute certain "data" about aspects of your everyday. On their own, they present a fragmented and narrow idea of an everyday burdened by productive reasonings. However, when they come together, there is a potential for them to interfere with each other. The collected sense of a productive everyday does not end up producing a rational, lucid image, but rather an absurd portrait. The overlaps of the codes and systems attempt a language, but instead become layered, surreal, complex drawings of a layered and complex life.

Jay Kanti

Jay KantiFrom a scrutiny of your routines, what has emerged is that most practices are clearly delineated - time with family, time with friends, time with social media, time with social play (football), etc. The overarching escape from these routines lies in the solitary getaways on your scooter, often with you seeking out solitary routes in your neighbourhood and in the city. A documentation of this practice reveals another city altogether - a city that comes together from under canopies, a city of leftover spaces, a city of rest, a city glimpsed in passing. In order to reproduce this experience, you turn to making books which have the possibility, as material objects, to unfold in several ways in time and space. These books are able to hold the experience of these journeys and take many forms by working with folds, the measure of pages, light, texture, etc.

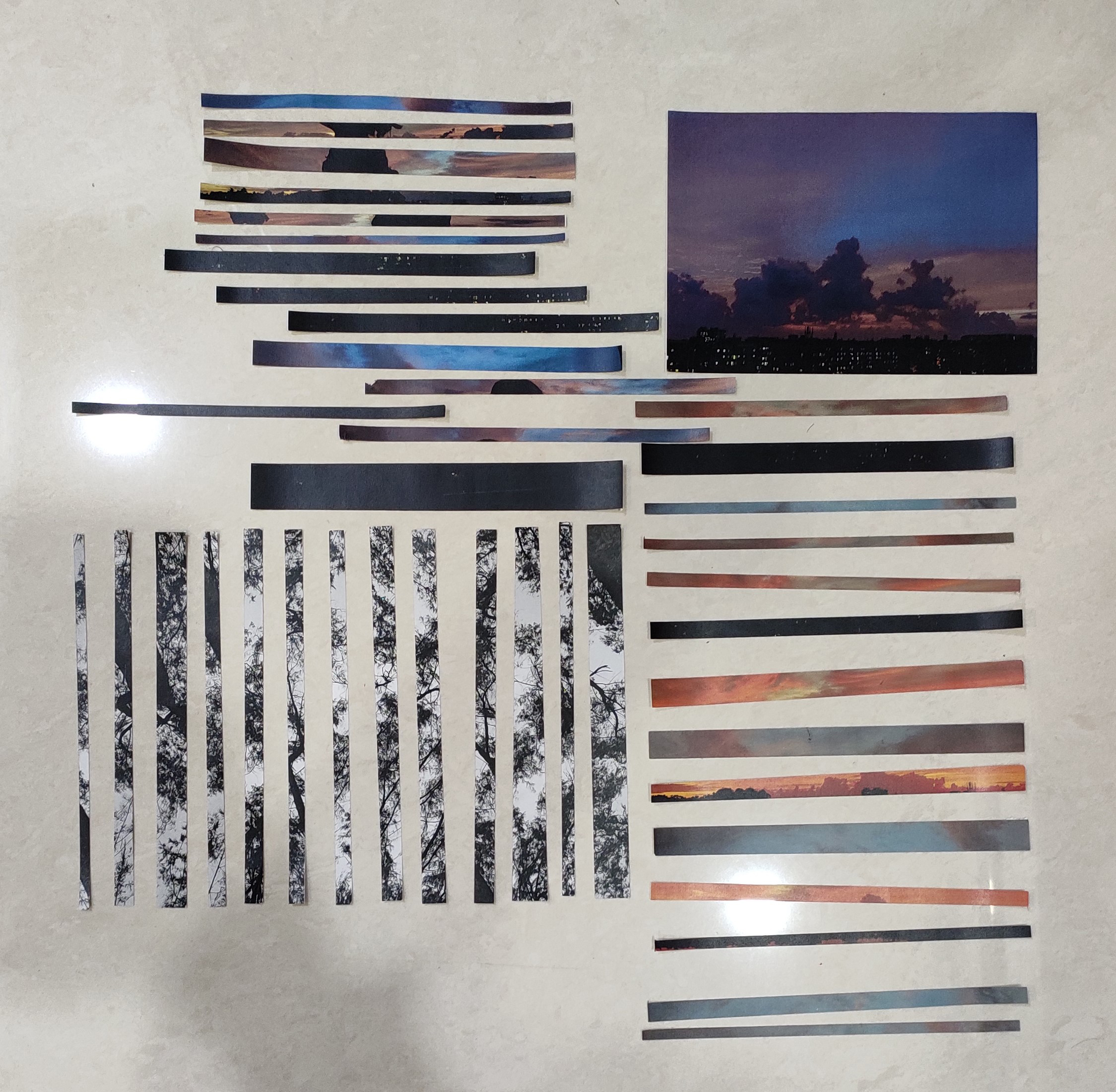

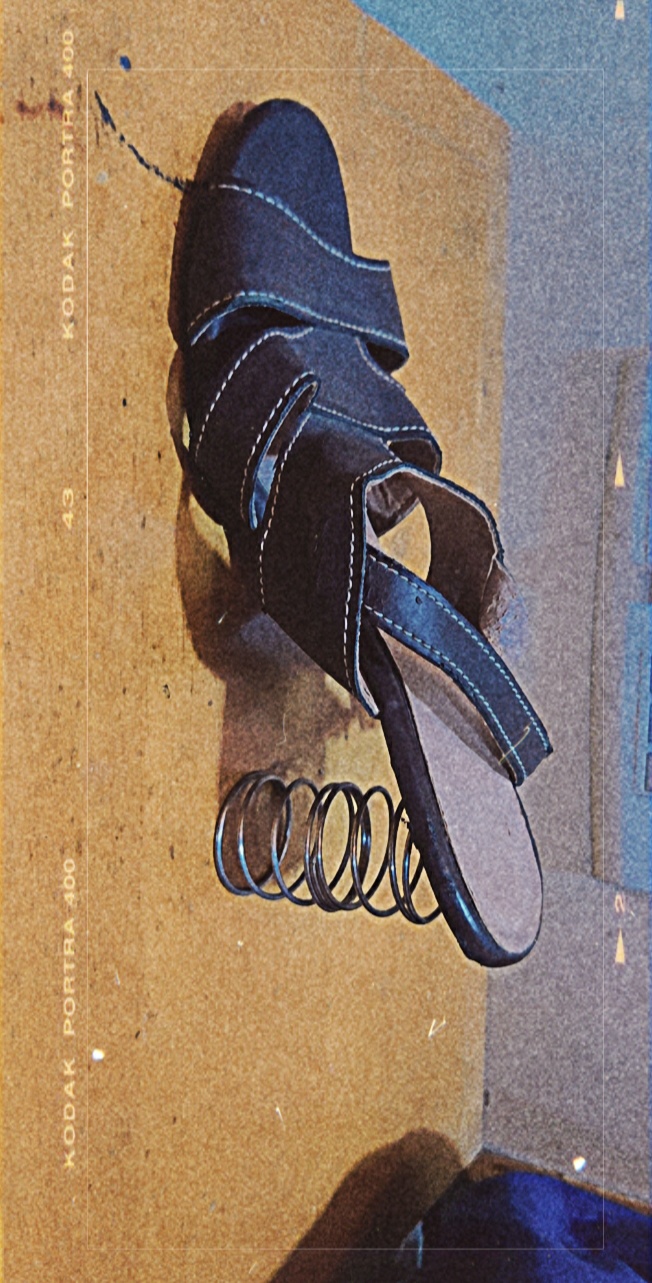

Sakshi Sawant

In an effort to make space for the collection in your everyday life, the collection needs to be exhumed from the benign ways in which you have currently stored it. They are in boxes, neatly stowed away in cupboards, rarely thought of or understood. Once you begin to take them from their resting places, they present opportunities for you to see everyday objects in newer, more exciting ways. Your routine then takes on a strangeness when these objects from your collections come in conflict with your practices, resulting in sculpture and prosthetics and all manner of surreal hijacks of mundane activities.

Jinal Trivedi

Your practice comes from a playful engagement with experimental drawing. At this point, your primary concern is how movement translates into drawing, how time and dynamism is able to be held in the space of the paper. Towards this, you start by tracing everyday movements. Care is taken to ensure fidelity to the movement; the radius of the gestures, the force with which they enact, all of these become important in the construction of the drawing. What has emerged till now is a series that looks in great depth at the ways in which we perform routine, from an idea of the intimate (braiding hair, settling on the bed), to the idea of the domestic (scrubbing floors, cutting vegetables). Potentially, this could take many directions - bring in collaborative movements, non human movements, grow exponentially in scale or become ways to explore minute scratches and grazes on a surface. The work here, at this point, looks at the immediate everyday / domestic practices as the field for thinking through movement in drawing.

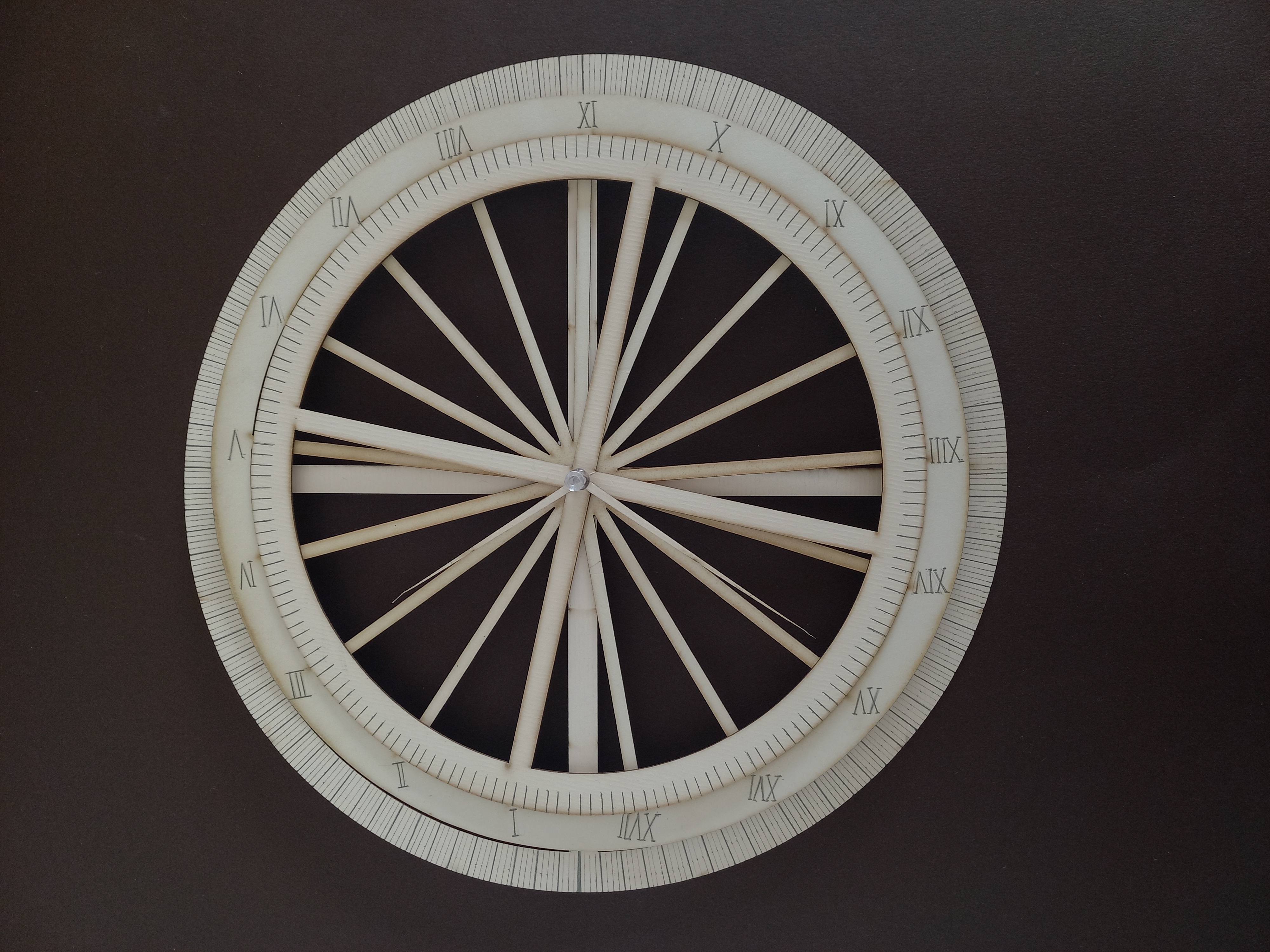

Riddhi Shah

Your question is located in a resistance to the productive idea of time. While life is lived through systems such as alarms and clocks, these systems are actually incredibly fragile and a sense of play is able to shatter the idea of a useful routine. Therefore, as a test, you consider building a seventeen hour day where certain units remain the same and others are stretched and / or compressed. The clock is an elaborate device. While working with the idea of a finite day, the dials and hands work with and against each other in order to elongate periods of rest and periods of leisure. To accommodate this, chores and "productive" activities get compressed, all the while giving the illusion of a complete day. Time is a construct, a myth that is easy to challenge and the practice intervenes in systems of measures to hold within it swollen periods of pleasure to hinder and confuse usefulness.